Some quotes you have seen so many times that after a while, you tend to think that the quoted remark was a collective invention, too good to be true. That’s what I thought for many years about Botvinnik’s famous remark about young Anatoly Karpov, who was admitted to Botvinnik’s class at the age of twelve: “The boy doesn’t have a clue about chess, and there’s no future at all for him in this profession.”

But my distrust was based on faulty memory, as I recently found that the first time I must have read this quote was in Karpov’s own book Karpov on Karpov from 1991. He hadn’t heard the disparaging remark from the Patriarch’s own mouth though, but it was related to him by Botvinnik’s assistant Yurkov.

Karpov liked to play blitz until late night and early morning. Botvinnik saw blitz games as a waste or even worse, as a slippery road to ineradicable superficiality. According to Karpov, Botvinnik presented himself as God, who would mold, refine and elevate the primitive raw material that was brought to him from the far Soviet provinces in a way that would make them unrecognizable compared to their former selves.

During his first lesson he told the young pupils that he was working on a computer program that in due time would beat grandmasters, even world champions. The boys shuddered. What would be left in chess for them?

Karpov writes: “Don’t worry, boys,” said Botvinnik. “You will get a job. After all, my computer needs strong chessplayers to be programmed. You will be among the first.” (I translate from the Dutch edition).

Karpov realized that after losing his crown, Botvinnik was plotting for revenge by developing a soulless chess murderer that would beat everyone in the name of his creator.

I browsed through Karpov’s old book at the occasion of the short match that he recently played against Jan Timman, from December 26 to 29 at the Groninger Museum. Playing chess in museums seems to be a trend, and it was not only picked up by the traditional Groningen chess festival, but also by the Tata Steel tournament, that on Wednesday, January 15, it will have one of its rounds at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

Karpov and Timman, both 62 years old, are still active players; Timman in classical chess and Karpov almost exclusively in rapid chess or blitz. This was a friendly match with a friendly time control: 40 minutes for the game plus an increment of 30 seconds per move. In the past, they had played two very serious matches, a Candidates final in Kuala Lumpur in 1990 and a FIDE World Championship match in the Netherlands and Indonesia in 1993, which was not the brightest chapter in the history of FIDE.

In 1993 Kasparov and Short, who had privatized their own championship match, played in London, more or less at the same time as the first leg of the match in the Netherlands between Karpov and Timman, who had been called in by FIDE as reserves.

Everything was well-organized in the Netherlands, or so it seemed. Organizers, commentators, people of the press office and many others were decently paid. But what about the players?

I still vividly remember the press conference where the Dutch head of the organizing committee sadly announced that though they had done their best to find sponsorship for the prize fund, they had in fact not been able to find even a penny. It was quite a shock for the journalists present, and they could well imagine the state of shock that Karpov and Timman would experience. But there still was Oman, which supposedly had offered a prize fund of a million dollars for the second half of the match.

But not so. A few days later, FIDE president Florencio Campomanes regretfully announced that the deal with Oman was off. In fact it later transpired that it had never been on. Campomanes’ sad announcement came after the tenth game. There were two more games to go in Amsterdam, and twelve more games in nowhere-land. For Karpov and Timman, there was no money in the Netherlands – and both of them had spent already a lot to pay their seconds – and no obvious place to go to continue their match.

Karpov was two points up and approached Timman to explain his predicament. Of course he wouldn’t want to lose a game of the two that were still to be played in Amsterdam, but on the other hand, it would suit him even less if he would win one more game, as in that case the match would be practically decided and there would be no sponsor in the world who would throw money to a done deal.

Sensible words. No wonder that the last two games in Amsterdam ended in a draw, game 11 after only 11 moves and game 12 after what may have looked as a long, hard fight. But look at Karpov’s clever 32.Bc5. What is the purpose of that move? The only purpose was to allow Timman to play 32...Bd5 – otherwise refuted by 33.Rc7 – and exchange all rooks.

FIDE managed to lodge the second half of the match in Jakarta, Indonesia, with a prize fund of a million Swiss francs, which came out of FIDE’s own cashbox after some clever shuffling of funds.

Karpov had won both of his earlier matches against Timman and it would have been nice for the Dutch fans of Timman if he would have won at least this friendly match, but that was not to be. The first three games looked well-played but uneventful, unless you took a closer look at game 2, or followed the computer evaluation.

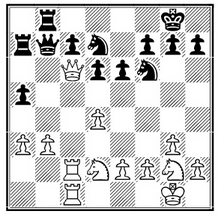

Karpov-Timman

ame 2 after 44...h4

Timman had been playing for a win for some time and had carelessly played 44...h4, after which Karpov could have won the rook, or the queen against his own rook, with 45.f3. After 45...Rxe3 he would win Black’s queen with 46.Rh8+, and after 45...Re6, the rook with 46.f5. He missed this chance, played 45.Rd6, and after 45...Qf5, the game ended as a draw ten moves later.

Karpov-Timman

Game 4 after 20.Rbc2

White has a small edge, but after the normal 20...Qxc6 21.Rxc6 Rbb7, his advantage wouldn’t have been too serious.

But inexplicably, Timman played 20...h6, and after the obvious 21.Qxc7 Qa6 22.Qc4, Karpov brought home his pawn advantage.

“Inexplicably,” I wrote, but there may be an explanation, as later that day it emerged that Timman had played the whole game with a broken hand. After the game, he went with the chief organizer Jan Colly to a hospital and a bit belated he came back to be interviewed by chess host and IM Hans Böhm with his hand in plaster and his arm in a sling.

Curiously, in 2005 Timman had already missed a Dutch championship because he had a broken hand. When asked if he really couldn’t play, while in the past he had once played a tournament with a broken leg, Timman answered that a chessplayer doesn’t need his leg to make a move, but he does need his hand.

But better beware, Old Shatterhand. Once more, and you’ll be in the Guinness Book of Records.

Click to play through the games