Ah, the good old days. About the series of matches that Charles Mahé de la Bourdonnais and Alexander McDonnell played in 1834 at the Westminster Chess Club in London, I have read that Labourdonnais chattered with the spectators while the slow McDonnell was pondering his moves. Occasionally the spectators approached the board of these two players, who were considered the best in the world, to give their own opinion on the position, sometimes moving the pieces. Or so it is said.

I am not saying that I long for such extreme informality. I have played in tournaments where journalists walking around on the stage were extinguishing their cigarette butts in our ashtrays. Too much informality, even for me. But when a chess tournament is played in a café, I have the pleasant feeling that chess is returning to its roots.

This year’s Batavia tournament, like the five previous tournaments that were played at the café Batavia1920, was by far not the strongest tournament in the world. It had four grandmasters, four international masters, a women grandmaster, Alina l’Ami – the wife of grandmaster Erwin l’Ami – and a Fidemaster, the 14-year old Jorden van Foreest, who would score an IM norm in this tournament and might have finished on a shared first place had he been less impetuous and overconfident in critical situations.

It was not a super-tournament, but it was played at a top location, opposite Amsterdam’s Central Station. Standing outside the café I was reminded of a novel of the Dutch writer A.F. Th van der Heijden in which the main character, a lawyer, whenever he arrives at the station, already smells the vodka that he will enjoy in the Amsterdam cafés. Looking to my left I saw the St. Nicolas church, where the ship of Saint Nicolas and Black Pete used to board to bring gifts to the children who had been good. To my right, I saw the Chinese quarter of Amsterdam. I visited the Batavia tournament as often as I could.

The highest seeded player was Dutch GM Sipke Ernst, but he didn’t do very well. Every day he commuted by train between Amsterdam and his home town Groningen, which meant that he would spend at least six hours a day travelling. Who could be as crazy as that?

Well, I knew one who was, our late and lamented grandmaster Hein Donner (1927-1988) who used to be called Big Brother by Genna Sosonko, which neatly rendered his function in Dutch chess.

From 1969 till 1981, the Dutch championship was played in the Frisian capital Leeuwarden, the first time in an old and venerable but rather derelict hotel called The Klanderij. Later Donner was to call it a typical example of “Olde Frysk Swine Cunt” architecture.

During one of the first rounds, a big piece of concrete fell from the ceiling into the spectator’s space. It was early in the round, there were not many spectators yet, and that was the only reason no one was killed.

All of us were looking like sheep at the havoc; only Donner had acted wisely by immediately jumping for cover under his table. Later he explained that this reflex was a left-over from World War II, when a few times he had had to seek cover from Allied bombings.

Later that day construction engineers told us that we could safely continue our tournament and after some resistance even Donner gave in.

During all these years that we played in Leeuwarden, after each round Donner would take the last train to Amsterdam, which meant that he also would be travelling six hours a day. In Amsterdam, he went to the artist’s club The Kring to play a few rounds of bridge, but not for too long, as the next morning he would have to take the train to Leeuwarden again. The other players in the Dutch championship thought he was mad.

Sipke Ernst, commuting to Groningen every day, had played in the previous months’ two tournaments in Costa Rica and one in Iran, winning all of them. He wanted to sleep in his own bed for a change, the bed where his girlfriend also slept. What’s the difference if I prepare in the train or in a hotel, he said in the early days of the tournament, but soon he learned better.

But in the last round he won a very interesting game against the Dutch IM Twan Burg. Had Burg won that game, he would have scored a GM norm and won the tournament. He got his chance, but he was nervous and lost.

The tournament was won by the Australian GM David Smerdon, who might be called half-Dutch. He has been living in Amsterdam for the last few years and recently finished his studies at the Tinbergen Institute (named after a famous Dutch economist) with a thesis called Everybody’s Doing it. It’s about copying dubious norms and bad practices and maybe Sipke Ernst should have read it before he copied Hein Donner’s mad travelling schedule.

You’ll find some games in the game viewer, but here are two snapshots.

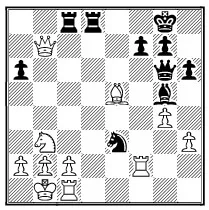

Merijn van Delft – Alina l’Ami, Round 1

Yochanon Afek, who wrote the daily reports on the website batavia1920.nl/chess, awarded the best game prize to this game, not so much because of the mating combination at the end, nice though it is, but for the way L’Ami conducted her attack after an intuitive pawn sacrifice in the early middlegame.

The game ended with 30…Nxc2 31. Rfxc2 Qxc2+ 32. Rxc2 Rd1+ 33. Rc1 Rdxc1+ 34. Nxc1 Rxc1 mate.

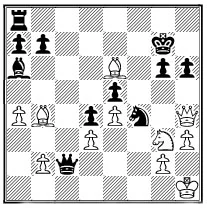

Simon Williams – Alina l’Ami, Round 9

Here White played 34. Nf5+ which led to a draw by perpetual check within a few moves. He had missed 34. Bf8+, with a mate in four.

Click to play through games: